Understanding ethnic inequalities in mental health

Originally published in The Doc Suit Debrief.

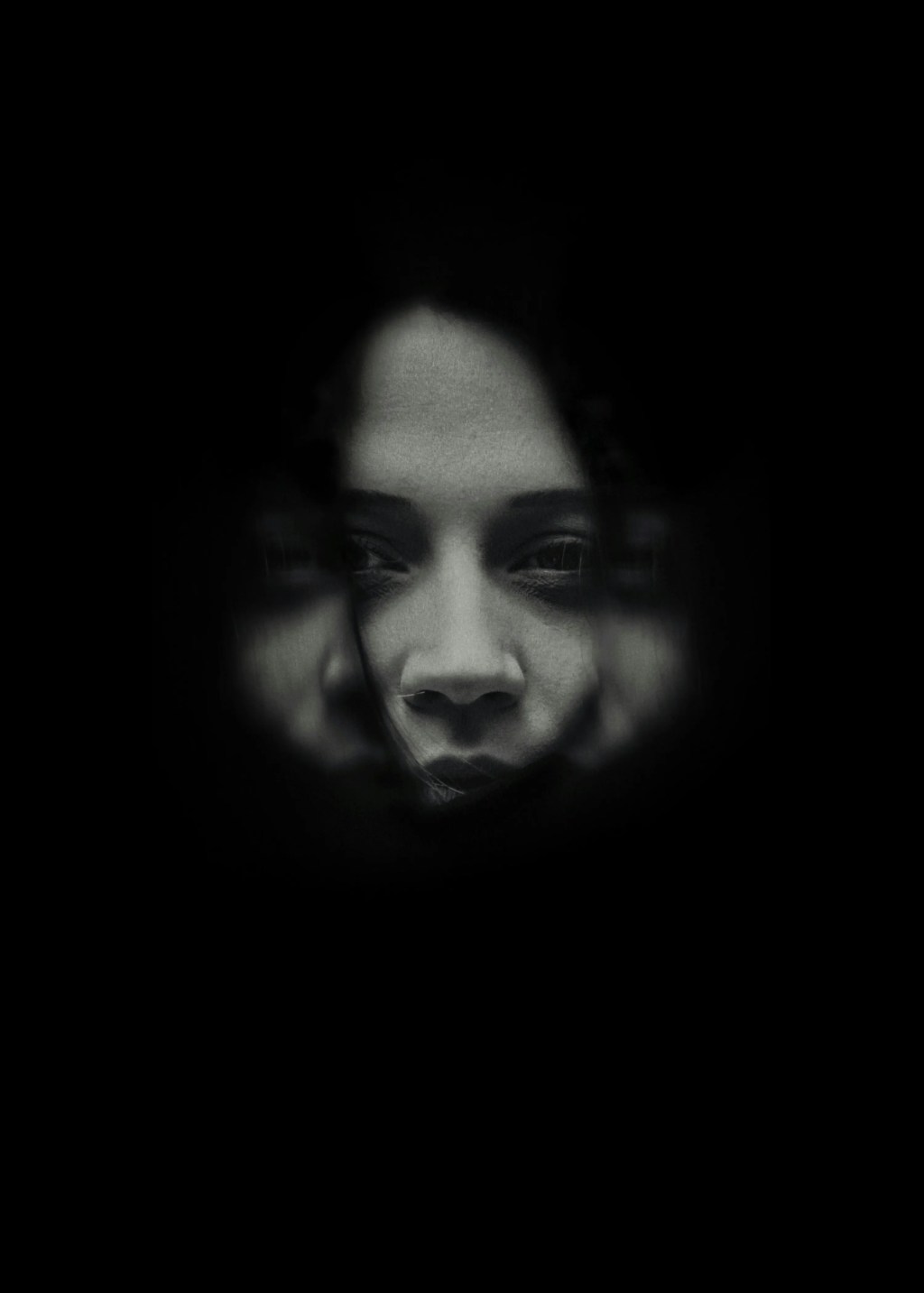

Imagine that there are two patients who arrive in A&E, both saying the same thing. They are feeling on edge and concerned with an impending sense of doom. One is diagnosed with acute anxiety, comforted with a cup of tea, and sent home with reassurance. The other is diagnosed with paranoid psychosis and detained under the Mental Health Act. The symptoms were identical. The difference? Their ethnic origin.

This is unfortunately a known pattern in the UK’s mental health services, with some ethnic groups being overdiagnosed and disproportionately detained under the Mental Health Act. But what’s going on? And why is this the case?

The Problem:

Research shows that black people are 3.5 times more likely than white people to be detained under the Mental Health Act. Black people often enter mental health services through police contact rather than a GP referral, and are 40% more likely than white people to enter mental healthcare via the criminal justice system. This is equivalent to 228 vs 64 detentions per 100,000 people, based on data from the UK Mental Health Services Data Set. This is, sadly, true for children as well as adults. Black children are 10 times more likely than white children to be referred to CAMHS – Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, “via social services rather than their GP service”, based on NHS research.

As well as these inequalities in how patients are managed within mental healthcare, there are inequalities in mental health outcomes. For example, 67.3% of white people “reliably improved” following anxiety and depression treatment, compared to 61.1% of Bangladeshi and 61.5% of Pakistani people, based on data from the UK Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) dataset. In fact, based on the same dataset, 8-9% of Bangladeshi and Pakistani people “reliably deteriorated” following anxiety and depression treatment.

This begs the question, if the treatments are the same and symptoms are the same, why are there such stark differences in people’s experiences of the mental healthcare system by ethnicity?

What’s going on?

Whilst the UK NHS provides equal access to healthcare for all, various social determinants, such as diversity in socioeconomic status, ethnicity, among other demographic factors, mean there are inequalities in healthcare outcomes.

Research shows that people exposed to compulsory admission and treatment (CAT) suffer from “epistemic injustice and racialisation” and treatments are often not culturally sensitive, with excessive policy and coercive care. Written evidence from the UK Parliament, under the UK Mental Health Bill’s written evidence, shows that there is a perception that black men in particular are seen as “problematic or in need of greater surveillance and monitoring”. Even if the presentation of symptoms is the same, the diagnosis and healthcare outcomes are different. This also creates a vicious cycle. Without a supportive conversation from the GP, entering mental health services via a coercive first experience breeds mistrust in both mental health services and the criminal justice system. This could result in avoiding mental healthcare services because of negative experiences, then presenting later when they are in a worse, more severe state. This then reinforces the perception that they are “problematic” or in “need of surveillance” and higher risk, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy that’s difficult to break. This reinforces mental health stigma, results in more extreme treatments, and establishes mistrust in the mental health system.

Other explanations that researchers have found include increased risk of poor mental health because of socioeconomic adversity in certain ethnic groups. This includes but is not limited to experiences of racism, discrimination, poor living conditions, and the stress of migration. These factors could reduce trust in the mental healthcare system, have linguistic barriers to accessing healthcare, as well as structural barriers based on socioeconomic background.

Research now suggests that there are multiple factors at play, of epistemic injustice, bias, as well as social determinants of mental health outcomes, which inflate certain diagnoses, and result in unequal treatment outcomes.

What needs to change now?

The first step is recognising these mental health disparities, which the NHS, UK Parliament, and several academic research papers have done. The next steps include addressing some of these problems directly. This can be done by implicit bias identification in the criminal justice system and for clinicians. Additionally, increasing representation and diversification in mental health research and clinical work so that we can better reflect the communities served. Furthermore, services should also monitor their diagnostic patterns and referral systems by ethnicity, to recognise any disparities and understand why that is the case.

Regardless of the exact combination of causes, whether that’s related to a bias in referral and diagnosis, or structural racism, it is clear that there are stark mental healthcare disparities in the UK by ethnicity. Their experience of the mental health system is often worse, with more coercion and less trust in the system. The blame doesn’t fall on any individual, but rather the systemic factors at play here should be recognised, and more importantly, understood at their core, in order to prevent harm to patients and equalise mental healthcare treatment.

This article was originally published in The Doc Suit Debrief on January 16th, 2026.